CPM envisions a world where mathematics is viewed as intriguing and useful, and is appreciated by all; where powerful mathematical thinking is an essential, universal, and desirable trait; and where people are empowered by mathematical problem solving and reasoning to solve the world’s problems.

CPM’s mission is to empower mathematics students and teachers through exemplary curriculum, professional development, and leadership. We recognize and foster teacher expertise and leadership in mathematics education. We engage all students in learning mathematics through problem solving, reasoning, and communication.

In a perfect world, every student would have the opportunity to learn math by being engaged and challenged. We are working to make this possible: More math for more students! CPM does not aspire to be the biggest publisher, but we do believe we are among the few who truly put student learning first.

CPM began when a few university professors were awarded two Eisenhower grants. These professors came together with 30 math teachers around Sacramento, California in a grassroots effort to change the way mathematics courses were taught.

Read more below.

In response to the wide range of curricula claiming to be research-based, Dr. Clements (2007) articulated a framework outlining phases for developing research-based curricula (Clements, 2007; Sarama & Clements, 2019). This peer-reviewed framework was published in NCTM’s prestigious Journal for Research in Mathematics Education. Sarama & Clements (2019) further extended this research, arguing:

“We need scientific approaches to the conceptualization, design, creation, implementation, and scale-up of curricula that are not just ‘based on’ or ‘validated by’ research but that were constructed, refined, and evaluated with a comprehensive program of research and development.

A curriculum development program should address not only the practical question of whether the curriculum is effective in helping children achieve specific learning goals but also the conditions under which it is effective. Theoretically, the research program should also address why it is effective and why certain sets of conditions decrease or increase the curriculum’s effectiveness.

A core feature of the [Curriculum Research Framework] is that it is grounded in coordinated interdisciplinary research… to scale-up [across 10 phases]… Each phase must yield positive results to proceed to the next.” (pp. 144-145)

While CPM predates this Curriculum Research Framework, it aligns with many (though not all) of the phases described. CPM continues to pursue research from multiple domains—such as cognitive science, psychology, mathematics education, and learning sciences—to inform curriculum and professional learning design, evaluate effectiveness under various conditions, and contribute to understanding how best to support mathematics teaching and learning at grades 6–12.

CPM was born with two Eisenhower grants between 1989 and 1995 when a group of 30 math teachers in and around Sacramento, CA, came together in a grassroots effort to change the way mathematics courses were taught. Within two years of the first grant, more than 500 teachers were using CPM materials, and within three years, well over 1,000 teachers were supported by CPM materials and professional development. By the end of the decade, CPM was a core curriculum in more than 20% of California schools. More importantly, teachers reported that after taking CPM’s Algebra 1 course, students no longer asked “What am I ever going to use this for?”—an indicator of meaningful mathematical experiences.

The original title of the program, established with the first Eisenhower Grant, College Preparatory Mathematics: Change from Within, reflected the growing requirement of algebra around the country as a high school graduation requirement. Change from Within reflected the grassroots of CPM’s design as by teachers, for teachers. The second Eisenhower Grant, College Preparatory Mathematics: Change through Assessment, aimed to support teacher learning around assessment—primarily, that teaching math differently requires assessing differently. The name College Preparatory Mathematics served to reassure teachers and parents that the courses were substantive treatments of traditional courses and were aligned with state standards. This was especially important as the national “math wars,” particularly in California, raged over how to teach K-12 mathematics.

Then, as today, many mathematics classes—particularly Algebra 1—were functioning as a filter, holding many students back from attending college. These teachers took action within their own classrooms to reverse this inequity.

Guided by three founders—two university professors, Drs. Tom Sallee and Elaine Kasimatis, and Judy Kysh, then director of the Northern California Math Project and current professor of mathematics education—the group’s goal was to transform algebra courses from a filter into a pump, creating opportunities for more students to attend college. The professors and teachers collaborated closely: Teachers deferred to professors for mathematical issues, while professors deferred to teachers on pedagogical matters. Together, they developed courses and professional learning workshops that gradually shifted mathematics instruction.

During the 1988–89 school year, the group met to discuss the California Mathematics Framework, a precursor to the 1989 NCTM standards. They also explored research on constructivism and collaborative learning. These discussions informed their understanding of how students best learn mathematics. Based on this research and years of classroom experience, the group established what are now known as The Three Pillars of CPM: Collaborative Learning, Problem-Based Learning, and Mixed Spaced Practice.

This examination of existing research aligns with Phases 1–4 of Clements’ framework. CPM is rooted in an analysis of the relationships between mathematics content, student thinking, and pedagogy (Phases 1–3). For Phase 4, Clements (2007) suggests curriculum content flow be based on models of student thinking developed through formal research. Such models, known as “learning trajectories,” began to emerge in the mid-1990s (Simon, 1995 PDF). Indeed, classroom-based studies rather than clinical or laboratory settings were just emerging at CPM’s inception, coinciding with growing interest in constructivist learning theories. According to Simon:

“Although constructivism provides a useful basis for thinking about mathematics learning in classrooms, it does not tell us how to teach mathematics. … [Learning trajectories research] contributes to a dialogue on what teaching might be like if it is built on a constructivist perspective on knowledge development. The specific focus of [learning trajectories research in mathematics education] is on decision making with respect to mathematics content and mathematical tasks for classroom learning” (1995, p. 4).

In this way, although CPM’s first materials predate this research, they were based on student thinking models generated by the pioneering CPM teacher-authors and founders. Discussions between teacher-authors, colleagues, and Judy Kysh about student responses to materials and teaching practices led to iterative refinement of the embedded hypothesized learning trajectories in CPM textbooks.

To design curricula that spurred student interest, engagement, and learning, the flow of content in CPM’s curricula is grounded in CPM teacher-authors’ collective experience (hundreds of years) thinking about students’ mathematical thinking. Even more, the models of students’ mathematical thinking that informed the design of the curriculum were also informed by research. In this way, CPM is based on trustworthy models of students’ thinking that characterize how students progressively construct and refine their understandings of mathematical concepts. The mathematical trajectory of CPM curricula is purposefully designed to support both deep, conceptual mathematics learning and procedural fluency. Described below are three takeaways from research that deeply informed the original development of CPM: Learners construct rather than acquire understandings, Learning is supported by starting with the big picture, and Narrative and mathematical storylines support aesthetic responses.

Research takeaway: Learners construct rather than acquire understandings

The founders and teachers leveraged brain-based research from the 80’s and 90’s on how people think. Some members of the original CPM group attended lectures by Marian Diamond of the Lawrence Hall of Science, and other scholars such as Marny Sorgen (author and former teaching colleague of CPM founder Judy Kysh) gave regular presentations to the group. Constance Kamii’s research on intellectual autonomy was also influential in the original design of CPM. Kamii developed Number Talks and was one of the first scholars to describe children’s cognition around addition and subtraction, particularly how children construct their own understandings regardless of how they are taught. In this way, CPM’s design helps teachers build on students’ logical thinking to help them construct understandings of canonical mathematical concepts.

Research takeaway: Learning is supported by starting with the big picture

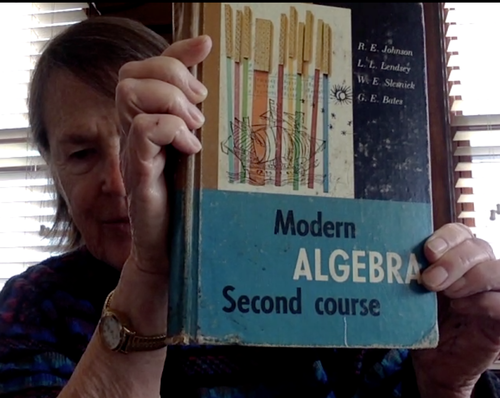

From reading, attending conferences, and soliciting researchers to give presentations on their findings, the group formed another key takeaway: Students learn mathematics best when they start with a big picture that has some sort of mystery to be uncovered. Beyond being supported by research, the veracity of this principle of learning was experienced firsthand by some of the original group. For example, founder Judy Kysh cites an Algebra textbook written by Johnson, Lendsey, Sleznick, and Bates (an Addison Wesley book) as having deeply influenced her thinking. Unlike most texts of the day, in which problems required pre-worked examples, this text allowed learners to solve new problems by reasoning from prior problems. Many problems in CPM’s original text were inspired by this textbook. They were also inspired by Judy Kysh’s (then Judy Salem) work on a Scott Foresman Algebra 1 and Algebra 2 textbook series (1984), in which each chapter began with a real problem and developed the necessary mathematics by the chapter’s end. Following this inspiration, CPM chapters were originally named for their real-world problems rather than the mathematics involved. Anecdotal evidence from student portfolios and interviews suggested students remembered mathematics by the problems they encountered, helping them solve similar problems in other contexts.

Research takeaway: Narrative and mathematical storylines support aesthetic responses

Over the years, building on more recent research, CPM materials have evolved to develop both narrative and mathematical storylines (e.g., Dietiker, 2013, 2016, 2019). CPM’s textbooks are designed so that mathematical and narrative storylines complement each other. Students encounter enigmatic situations—problems they initially cannot resolve. The mathematics in CPM texts is organized so students experience “aha” moments, fostering aesthetic dimensions of mathematics, such as feelings of curiosity and surprise, as they construct mathematical connections and elegant solutions.

From the peer-reviewed academic research described above, CPM synthesized three design principles that have since become known as The Three Pillars of CPM: Collaborative Learning, Problem-Based Learning, and Mixed Spaced Practice. Grounding the curriculum in these three pillars, the group wrote a new set of Algebra 1 material (aka Math 1) in five weeks in the summer of 1989, with an additional smaller team editing and polishing. During the 1989-90 school year, the teachers who worked on the materials piloted them and took notes on how to improve them, meeting nearly every month to share experiences and document improvements.

After this initial pilot, teachers revised the Algebra 1 materials and created the first Geometry text (aka Math 2) in the summer of 1990. They then piloted the revised Algebra 1 and new Geometry materials during the 1990-91 school year. The Algebra 2 text (aka Math 3) was initiated in the summer of 1992, undergoing two rounds of field-testing and review, with the final first edition completed in the summer of 1994.

Initially, CPM text materials were distributed by chapter as shrink-wrapped stacks of loose-leaf pages from the back of a van driven by founder Judy Kysh to a central location. Teachers gathered to collect their materials, participated in professional development sessions throughout the day, and returned to their schools to duplicate and distribute materials chapter by chapter to their students.

In 1993, when the quantity of materials began to exceed the capacity of Judy’s borrowed university van, CPM incorporated as a California nonprofit corporation, enabling the printing and sale of soft-bound Algebra and Geometry textbooks. This meant teachers no longer needed to copy and distribute materials at their schools.

CPM incorporated as CPM Educational Program, rather than College Preparatory Mathematics, since it was already commonly referred to as CPM. Teacher feedback also highlighted that all students—not only those bound for college—benefited significantly from learning with CPM materials. Therefore, courses and professional learning opportunities became universally known as CPM.

Many of CPM’s transformative professional learning experiences, including the Academy of Best Practices and the Teacher Researcher Corps, continue to be funded by textbook sales.

The soundness of CPM’s research-based design has been affirmed through external reviews. In 1999, the US Department of Education recognized CPM as one of the top twelve reform-based mathematics curricula (source). This evaluation focused on five mandatory criteria: engaging students in mathematical inquiry, focusing on mathematical content, appropriateness for high school students, using information technology for inquiry teaching and learning, and being supported by research.

CPM continues to be acknowledged as an exemplary curriculum. During 2013-2014, the California State Board of Education (CA BOE) evaluated CPM with its curriculum alignment tool, similar to the Instructional Materials Evaluation Tool, a rigorous Common Core-aligned curriculum evaluation tool developed by CCSSM standards author Jason Zimba (Achievethecore.org). This evaluation reviewed CPM’s middle-grade courses and Core Connections Algebra for mathematical alignment, program organization, assessment, universal access, instructional planning, and teacher support. This review resulted in California’s adoption of CPM for grades 6-8 and Algebra, prompting many districts to perform independent evaluations, including Geometry, Algebra 2, and Integrated I, II, and III.

Furthermore, CPM’s middle school series (Core Connections 1-3) and both high school pathways (Traditional and Integrated) have been evaluated by EdReports. Both high school pathways achieved the highest rating of “meets expectations,” while the middle school series received positive reviews. According to EdReports:

“The [Traditional and Integrated high school] materials attend to the full intent of the mathematical content standards and also attend fully to the modeling process when applied to the modeling standards. The materials also meet the expectations for rigor and the Mathematical Practices as they reflect the balances in the Standards and help students meet the Standards’ rigorous expectations and meaningfully connect the Standards for Mathematical Content and the Standards for Mathematical Practice.” (Integrated and Traditional high school series, see more Independent Reviews from EdReports and others.)

Due to CPM’s successful independent evaluations and strong reputation in supporting standards-based instruction, CPM was invited by university scholars nationwide to collaborate on the 2020 Gates Foundation Grand Challenge for Algebra 1, Balancing the Equation.

Today, CPM’s diversely qualified team is still guided by some of the original teachers who helped research, write, field-test, and revise the first versions of the curriculum. Holding true to its roots, CPM values and supports teachers as curriculum writers, teacher-researchers (TRC), and professional learning leaders (RPLCs) — and also has a research department that supports these efforts. Currently, CPM is looking into implementation and impact studies that account for its programmatic theory as another way to buttress its research base, although these may be delayed by COVID-19.

These future studies will meet the last six phases of the framework for research-based curricula. The last five phases include investigating the curriculum’s effectiveness with various student groups and teachers and investigating how it can be improved to serve diverse situations and needs.

CPM also funds non-evaluative external research as part of its CPM Research Grants Program, which aims to support research that contributes to the broad mathematics education community. Research from this program has contributed to both theory and practice in mathematics education, thus contributing to meeting two of the three emphases of the framework — theory, practice, and policy.

While materials are no longer distributed out of the back of a van, CPM’s dedication to translating research into practice, and commitment to the founding pillars of Collaboration, Problem-Based Learning, and Mixed Spaced Practice are still at the heart of CPM. With each new edition and series, CPM draws on available research to determine how to best support teachers to be successful in helping all students learn mathematics deeply, usefully, and permanently.

CPM originated in conjunction with two Eisenhower Grants and the Math Project.

Learn about how our research base started, our results, and efforts to support more educators!

CPM has its first Summer Leadership Institute.

Participate in our engaging and teacher-led initiatives!

CPM Professional Learning is officially accredited by the Middle States Association Commission on Elementary and Secondary Schools (MSA-CESS).

Learn more about our accreditation process and how you can earn continuing education credits through us!

The Inspiring Connections middle school courses are standards-based and organized around engaging, team-worthy, non-routine problems.

Learn more about this new middle school curriculum.

2.3.4

Defining Concavity

4.4.1

Characteristics of Polynomial Functions

5.2.6

Semi-Log Plots

5 Closure

Closure How Can I Apply It? Activity 3

9.3.1

Transition States

9.3.2

Future and Past States

10.3.1

The Parametrization of Functions, Conics, and Their Inverses

10.3.2

Vector-Valued Functions

11.1.5

Rate of Change of Polar Functions

This professional learning is designed for teachers as they begin their implementation of CPM. This series contains multiple components and is grounded in multiple active experiences delivered over the first year. This learning experience will encourage teachers to adjust their instructional practices, expand their content knowledge, and challenge their beliefs about teaching and learning. Teachers and leaders will gain first-hand experience with CPM with emphasis on what they will be teaching. Throughout this series educators will experience the mathematics, consider instructional practices, and learn about the classroom environment necessary for a successful implementation of CPM curriculum resources.

Page 2 of the Professional Learning Progression (PDF) describes all of the components of this learning event and the additional support available. Teachers new to a course, but have previously attended Foundations for Implementation, can choose to engage in the course Content Modules in the Professional Learning Portal rather than attending the entire series of learning events again.

The Building on Instructional Practice Series consists of three different events – Building on Discourse, Building on Assessment, Building on Equity – that are designed for teachers with a minimum of one year of experience teaching with CPM instructional materials and who have completed the Foundations for Implementation Series.

In Building on Equity, participants will learn how to include equitable practices in their classroom and support traditionally underserved students in becoming leaders of their own learning. Essential questions include: How do I shift dependent learners into independent learners? How does my own math identity and cultural background impact my classroom? The focus of day one is equitable classroom culture. Participants will reflect on how their math identity and mindsets impact student learning. They will begin working on a plan for Chapter 1 that creates an equitable classroom culture. The focus of day two and three is implementing equitable tasks. Participants will develop their use of the 5 Practices for Orchestrating Meaningful Mathematical Discussions and curate strategies for supporting all students in becoming leaders of their own learning. Participants will use an equity lens to reflect on and revise their Chapter 1 lesson plans.

In Building on Assessment, participants will apply assessment research and develop methods to provide feedback to students and inform equitable assessment decisions. On day one, participants will align assessment practices with learning progressions and the principle of mastery over time as well as write assessment items. During day two, participants will develop rubrics, explore alternate types of assessment, and plan for implementation that supports student ownership. On the third day, participants will develop strategies to monitor progress and provide evidence of proficiency with identified mathematics content and practices. Participants will develop assessment action plans that will encourage continued collaboration within their learning community.

In Building on Discourse, participants will improve their ability to facilitate meaningful mathematical discourse. This learning experience will encourage participants to adjust their instructional practices in the areas of sharing math authority, developing independent learners, and the creation of equitable classroom environments. Participants will plan for student learning by using teaching practices such as posing purposeful questioning, supporting productive struggle, and facilitating meaningful mathematical discourse. In doing so, participants learn to support students collaboratively engaged with rich tasks with all elements of the Effective Mathematics Teaching Practices incorporated through intentional and reflective planning.